That joke is probably going to get overused this weekend.

That joke is probably going to get overused this weekend.

William Shatner and I and a few thousand of our closest friends will be in Houston this weekend for Space City Comic Con. Come find me with WordFire Press at booth 901!

That joke is probably going to get overused this weekend.

That joke is probably going to get overused this weekend.

William Shatner and I and a few thousand of our closest friends will be in Houston this weekend for Space City Comic Con. Come find me with WordFire Press at booth 901!

I do some creative work with Too Many Legs, a premier animation studio in Salt Lake City. My good friend and author / rocker Craig Nybo originally hooked me up with I an Johnston, Tim Rowberry, and the rest of the team, and I’ve had fun developing several animated TV series that are in various stages of being pitched to networks or investors.

an Johnston, Tim Rowberry, and the rest of the team, and I’ve had fun developing several animated TV series that are in various stages of being pitched to networks or investors.

TML’s artists are fantastic, and as of now, you can buy their work. Click here to see TML’s eBay page, featuring original animation art of the FIFA World Cup USA Womens Champions.

(Those are not the pieces showing in this post, which are promo art for kids’ TV shows I worked on).

Collect original artwork! Support an indie studio! Show your sporty feminist bona fides! Go, USA!

Collect original artwork! Support an indie studio! Show your sporty feminist bona fides! Go, USA!

Check it out.

Rob Wells is branching out into Indie publishing with his forthcoming novel Airships of Camelot! I think this is a great thing — as the industry changes, I think many professional authors will have fingers in various kinds of publishing and writing pies.

Rob Wells is branching out into Indie publishing with his forthcoming novel Airships of Camelot! I think this is a great thing — as the industry changes, I think many professional authors will have fingers in various kinds of publishing and writing pies.

I’ve read this book, and I love it. It’s a post-apocalyptic helium-punk retelling of the rise of young Arthur to kinghood, complete with mech warriors and airships. It’s in that plot- and character-driven space that is often labeled and sold as YA, but finds lots of adult readers, too.

So I welcome Rob to career in multiple markets, and I invite you to go check out the Indiegogo page. I’ve contributed, and I invite you to pitch in, too.

Debut novelist Brian Lindow has launched an epic of which C.S. Lewis would be proud.

Debut novelist Brian Lindow has launched an epic of which C.S. Lewis would be proud.

The Soulscape Code: Slags and Embers is the first of a series set in a ruined world. Deprived of its defenders (the three Forges of Light, Life, and Truth), the land has been ravaged and oppressed for hundreds of years by its three immortal Rifters (Darkness, Death, and Deceit).

But the transcendant forces of good have not forgotten the world. Now they raise up champions in the form of an unlikely collection of young misfits, including a runaway princess and a dead and resurrected assassin.

Lindow resembles David Farland or Brandon Sanderson in his approach. The fantasy and magic here are highly moralistic, and constructed around a vortex of interlocking conceptual opposites. In addition, the world is tiered into a series of three planes that impact each other: an individual’s internal Soulscape, the Terrascape of the physical world, and the Deisphere of the gods that surrounds it all. This is elaborate philosophical world-making, and well-built to tell tales of nobility and love.

With his tongue somewhat in his cheek, Lindow in his epilog says “I hope this will be the best starting book of which I am capable as well as the worst book I ever write.” If this is the worst book he ever writes, then he’s a writer to watch in the years to come.

I’m heading to Connecticut this week. I’ve spent a surprising amount of time in and around Hartford in the last year with corporate training clients, but this time I’m heading out for Connecticon. Here’s my tentative schedule:

Friday

2:40 pm How to Make It in the Industry

6:20 pm Workshop: World Building

Saturday

6:20 pm Literary Roundtable

Sunday

11:40 am Steampunk in Literature

The rest of the time I should be at the WordFire Press booth, selling books. Let me know if you’re planning to be there, too.

I’m a big proponent of self-driven learning. For a writer, I think that’s essential. So here are some of the non-fiction books I’ve read in the last couple of months.

Leibniz: An Intellectual Biography. I had never heard of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz until I read Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle (which you should read, if you haven’t already). Leibniz was part of that last generation of thinkers (in the European tradition) who could arguably know everything — he was a peer, and sometimes an antagonist, of Isaac Newton. And Leibniz wanted to know everything, and assimilate it into a single intellectual whole, and moreover to put it into practice for the benefit of humankind — theoria cum praxi being his lifelong motto. And he was hugely influential — the reason he and Newton tangled (Stephenson readers will remember) is because they both claimed credit for inventing calculus.

Leibniz: An Intellectual Biography. I had never heard of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz until I read Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle (which you should read, if you haven’t already). Leibniz was part of that last generation of thinkers (in the European tradition) who could arguably know everything — he was a peer, and sometimes an antagonist, of Isaac Newton. And Leibniz wanted to know everything, and assimilate it into a single intellectual whole, and moreover to put it into practice for the benefit of humankind — theoria cum praxi being his lifelong motto. And he was hugely influential — the reason he and Newton tangled (Stephenson readers will remember) is because they both claimed credit for inventing calculus.

Leibniz’s own writing can be dense, and some of his ideas difficult to access. But Antognazza’s biography is very readable, and ties many of Leibniz’s ideas together in a narrative of his life as a courtier, correspondent, librarian, thinker, lawyer, theologian, and mine engineer.

Bonus: aging Leibniz was ahead of his time for fabulous wardrobe, dressing in fur stockings (to combat gout).

A History of Venice. For a long time, Lord Norwich’s one-volume history of Venice was the standard. It may still be that (I’m no expert), but in any case it’s still a highly readable account of the rise, fall, and eventual groveling surrender (to Napoleon) of the Venetian Republic.

A History of Venice. For a long time, Lord Norwich’s one-volume history of Venice was the standard. It may still be that (I’m no expert), but in any case it’s still a highly readable account of the rise, fall, and eventual groveling surrender (to Napoleon) of the Venetian Republic.

I came to this book by way of an interest in Byzantium, which began with a trip seven years ago to Ravenna. Northeastern Italy has deep and tangled history with Greece and Asia Minor, of which I had been basically ignorant. Lord Norwich’s (yes, he is a viscount and an English peer) three volumes on Byzantium were a great introduction to a lay person (Greek-, Italian-, and Latin-reading, not not a historian), and I wishlisted his book on Venice.

I finally read it this spring. The book has limitations, focusing as it does more on political figures than on the merchants and manufacturers who have arguably been as important as the doges, but it sets out the republic’s history concisely, clearly, and with the compassion that I think the best historians must have.

The Quest for the Historical Israel: Debating Archaeology and the History of Early Israel. This book is a sort of verbal duel between two archaeologists, and it’s fascinating.

The Quest for the Historical Israel: Debating Archaeology and the History of Early Israel. This book is a sort of verbal duel between two archaeologists, and it’s fascinating.

For those of you who may not have been following it, the archaeology of Israel has been going through tumultuous times as it has matured. Archaeologists now lie scattered along a spectrum that runs from

The duel here is between Amihai Mazar (conservative) and Israel Finkelstein (moderate revisionist), which is to say, by proponents of points of view in the middle of the spectrum. There is large agreement between them, but the points of disagreement are noted and interesting (on David’s Jerusalem, Finkelstein says it was a small village capital of a highland chieftain, and Mazar says we can’t know, because we haven’t found it yet; on the United Monarchy, Finkelstein says it never exited and is the retrojection of the real first Israelite state, Israel under the Omrides, while Mazar says the jury is still out).

The duel here is between Amihai Mazar (conservative) and Israel Finkelstein (moderate revisionist), which is to say, by proponents of points of view in the middle of the spectrum. There is large agreement between them, but the points of disagreement are noted and interesting (on David’s Jerusalem, Finkelstein says it was a small village capital of a highland chieftain, and Mazar says we can’t know, because we haven’t found it yet; on the United Monarchy, Finkelstein says it never exited and is the retrojection of the real first Israelite state, Israel under the Omrides, while Mazar says the jury is still out).

Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning. If you’ve followed me on social media at all, you know I like observing the rotating heavens. Allen’s book is a compendium of names of stars and constellations, along with astronomical data about them, organized by constellation.

I felt like a gull picking over a garbage dump reading this book. There’s a lot of data in here I’ll never care about, but there are gems, too. Cancer was once of the Gate of Men, through which the ancients thought humans descended from the sky to be born. And Capricorn (associated with the scapegoat / Azazel of Leviticus 16) was the Gate of the Gods, through which they eventually ascended to become immortal.

Bonus: a section up front compiling famous authors’ laughable astronomical mistakes.

I’ve just read Tolkien’s recently-published story The Children of Húrin. I don’t have a lot to say about it: in tone and voice, it’s somewhere between The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings, so if you liked The Silmarillion you may like this one, and you liked The Lord of the Rings you might. I don’t want to give away spoilers, but I will say that there are famed swords here, dark lords, elves, dwarves, and a dragon to be slain.

I’ve just read Tolkien’s recently-published story The Children of Húrin. I don’t have a lot to say about it: in tone and voice, it’s somewhere between The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings, so if you liked The Silmarillion you may like this one, and you liked The Lord of the Rings you might. I don’t want to give away spoilers, but I will say that there are famed swords here, dark lords, elves, dwarves, and a dragon to be slain.

But this is dark stuff. This is the tragic-germanic side of Tolkien, in full Beowulf mode, where the hero who is fated to slay Glaurung the dragon is also doomed to perform dark, dark deeds, and ultimately to die by his own hand.

Oh, shoot, that’s a spoiler.

The thought I had as I finished this book is that it gives the lie to Moorcock’s criticism that Tolkien wrote “epic Pooh,” high church Anglican Toryism dressed up as fantasy. This stuff is as dark and hopeless as any Elric story.

Which is kinda awesome.

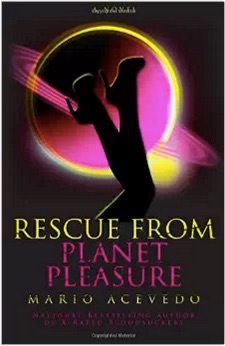

Felix Gomez is ex-military, a hard-nosed PI who operates on the borderlands between the natural and supernatural worlds, among Anglo and Mexican and Native American traditions, and sometimes between different planets.

Felix Gomez is ex-military, a hard-nosed PI who operates on the borderlands between the natural and supernatural worlds, among Anglo and Mexican and Native American traditions, and sometimes between different planets.

And he’s a vampire.

Felix’s friend Carmen is being held prisoner on the distant planet of D-Galtha, whose warrior natives need her outrageous sexiness to re-charge their libidos, that have diminished from neglect. It’s up to Felix and fellow vampire adventuress Jolie, transported into deep space by the magic of Coyote and La Llorona (with an assistant from a Navajo skin-walker arms merchant), to rescue her.

Mario Acevedo’s Rescue from Planet Pleasure is not the first Felix Gomez novel, but it stands alone well. It’s not for kids, sensitive people, or lit fic aficionados, but if you’re looking for a hilarious, no holds barred mashup adventure story, it’d be hard to do better.

“[O]nce upon a time (my crest has long since fallen) I had a mind to make a body of more or less connected legend, ranging from the large and cosmogonic, to the level of romantic fairy-story — the larger founded on the lesser on contact with the earth, the lesser drawing splendor from the vast backcloths… I would draw some of the great tales in fullness, and leave many only placed in the scheme, and sketched.”

— J.R.R. Tolkien, 1951